Engineering Identity: Between China's Speed and America's Proceduralism

A personal narrative and reflection on Dan Wang's "Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future"

My fascination with the macro has always stemmed from the micro. As the trade war between the U.S. and China swings back and forth, I can’t help but think of my own oscillating attitude toward my Chinese-American identity. I was in Beijing in 2008, celebrating the culmination of the country’s triumphant debut on the global stage; now, in Washington, D.C. in 2025—amid new immigration restrictions, National Guard deployments, and an increasingly combative foreign posture—the world feels as if it has tipped from one extreme to the other.

This essay explores the deeply personal tensions that emerge when geopolitics and identity intersect—how family histories are part and parcel with national narratives, and how personal memory refracts global change.

Dan Wang’s Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future has taken the tech, China, and foreign policy communities by storm. In it, Wang contrasts the U.S. as a “lawyerly society” with China as an “engineering state” to frame his observations on each country’s approach to infrastructure and governance. Part policy analysis, part personal memoir, the book sent me spiraling down my own thread of personal and historical reflection.

Wang argues in the first chapter that the worst year to be born in modern China might be 1949. My grandparents were born in the mid-1940s, during the tail-end of Japanese invasion and at the dawn of civil war. Growing up, my laoye (maternal grandfather) would sneer at the “Japanese Devils,” spit flying from his parched lips like sunflower seed shells.

Under the promise of Maoist communism, my laolao (maternal grandmother) endured the Great Famine of the 1960s. I picture her scavenging for tree bark and leaves, knee-deep in muddy water. Perhaps that image is a dream, but the Great Famine raged roughly from 1958 to 1962, and a great flood of the Hai River devastated Hebei province in 1963.

She lived through the Cultural Revolution, which stripped away her family’s wealth and barred her from higher education. She married my laoye—who despite their lifelong bickering, was her best leg up from a social status standpoint. (Today, he’s plagued with night terrors of the red guards chasing dissidents down the hallways.) They moved to rural Hebei, where she taught at a school—the sole remnants of her love of learning. If she couldn’t fulfill her dreams, she would raise a daughter who could.

My parents were children of Deng Xiaoping’s opening and reform era. In a country emerging into the global market yet still steering youth toward the sciences, my mother studied business. As an internal auditing manager at China Construction Bank, she traveled across the country assessing internal controls. In the background, Hong Kong was handed back to China; across the Sam Chun River, Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone began to sprout skyscrapers across the horizon.

“It’s so great to have both a son and a daughter,” my mom would tell my brother and me. Sometimes I imagine her in an alternate universe—still in China, still ambitious—facing the one-child policy that brought mass sterilizations, forced abortions, and infant deaths. Would I have no younger brother? Or would I, as the eldest daughter, have been aborted?

In fourth grade, my mom drove past a Planned Parenthood, where pro-life protestors stood chanting. Even at ten, I recognized the vehemence in her pro-choice beliefs.

In America, people are forced to give birth. In America, people take drugs to stave off overconsumption. A colleague once joked that even if he took Ozempic, he’d still gain weight. “I just eat out of boredom.”

It’s strange that in just a few generations, the collective goal shifted from starvation to restraint—a war against abundance. My body carries the memory of famine: it panics at hunger, ricocheting between scarcity and excess, epigenetic frugality and modern consumerism, until only shards remain.

It’s unimaginable to me to let food go to waste. “Every grain of rice matters,” my mom would say. It’s unimaginable to me to have children and not hope they’ll live better. What is today’s suffering, if not an investment in tomorrow’s welfare?

In the final chapter, Wang recalls his memories as an immigrant child in America. Every other line struck a chord.

“When we ate out, it was at Subway, which charged five dollars for a footlong sub.”

Every summer in middle school, my parents sent me to academic camps at the University of Washington. Instead of cash for lunch, they handed me a $100 Subway gift card. My order never changed: a six-inch Italian sub—no drink, no dessert. I haven’t eaten at Subway since. Now, when I order lunch at the office, I make it a three-course meal—a main, a side, and a drink or dessert. It pains me when my team picks sandwiches; I’m reminded of those monotonous, soggy loaves we ate because they were cheap and filling.

I recently learned that my parents now take weekend day trips together in the summer. Back when I lived at home, our outings always ended by lunchtime so they could rush back to cook.

“Now your dad refuses to eat at home,” my mom laughed. “He wants the full experience.”

“Really? That’s so different than before... What restaurants have you tried?”

“Oh, he just goes to Subway.”

On these day trips, my mom would pack Ziploc bags of fruit and nuts. She’d sometimes buy a pint of kefir if hunger strikes.

“In China, you can buy an entire meal for just two dollars.”

It was always in China this, in China that. Lately those statements have faded. I asked her again if she regrets coming to the United States. If she stayed in China, my brother and I wouldn’t have been born.

“I would’ve married someone else and had children regardless,” she told me over the phone.

Her cold words struck me speechless and choked-back sobs filled the gaps that words could not convey. As I cried silently, the other passengers on the metro stared.

Among my Chinese-American friends—children of H-1B visa holders—there’s a familiar “return to the homeland” narrative, where as a young professional, you visit China without the weight of family tying you to your hometown. It’s less common among descendants of earlier immigrants who opened Chinatowns, restaurants, and salons. Partly, it’s economics: the H-1B generation is more financially enabled, less bound to tight-knit communities. But it’s also that China today is prosperous, desirable—a place to travel, not just remember.

My brief version of this “return” came in January 2024, when I traveled with a white American friend to Beijing, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. The tale is timeless: high-speed bullet trains, frictionless delivery apps, cities pulsing with cutting-edge technology.

When I was five, I spent summers in China playing with bricks and sucking on cheap popsicles. Seeing the cityscapes now, I felt proud of the country, even though it didn’t belong to me. Now I understand why my grandfather—who still imagines Shenzhen as a fishing village—believes his homeland is the greatest power on earth.

“Rather I want Americans to experience what the previous generation of Chinese have felt: a sense of optimism about the future driven in part by physical dynamism. Chinese who have experienced the country’s blistering economic growth over the past four decades look to the past with pride and to the future with hope.”1

Rather than the modern flexes of grandeur, what impressed my friend most was the Great Wall—a living capsule of China’s enduring capacity to build. More than the wall itself, it was the symbolism of standing there: a throwback to the early 2000s, when China joined the WTO, opened its borders, and bilateral optimism felt within reach. It’s that version of the world I long for—where the air between the U.S. and China is not defensive, but curious.

For a long time, I perceived China’s speed and America’s proceduralism as being stuck in the worst of both worlds. I was a quiet doer in a country that prized loud debate, yet lived amid crumbling infrastructure and exorbitant cost of living. I was proud of China, proud of my Chinese heritage, but ambivalent about being in America.

The past six months have been a rediscovery of what being American means. PG is, as Wang describes, an American infused with Chinese-esque optimism and instinct toward action. He wants to make America great—not in the exclusionary way of Trump, but through curiosity and care. Curiosity not in the escapist sense, but tied to a responsibility to better America—in the same way Dan Wang looks to China’s engineering society for guidance on how to speed up the U.S.’s industrial manufacturing.

PG loves the neighborhood Moroccan restaurant more than any establishment he visited in Morocco. Not because the food is necessarily superior, but because the owner of the neighborhood joint embodies American pluralism—a country where cultural exchange lives in everyday breaths, where people from all over the world believe they can establish a livelihood.

In the Virginian suburbs, we’ve checked off soondubu, salteñas, turnip cakes at pushcart dimsum, Ethiopian platters, and Northern Vietnamese phó. In D.C., we’ve attended embassy events and China-centric book talks, savored a ten-course kaiseki, and carved into a 39-ounce Catalonian rib-eye. Through these adventures, I’ve come to love the nation’s capital and all that it represents.

My interest in China and America has less to do with hard power or military might. What fascinates me instead are the experiential and cultural dimensions—hospitality, food, and the quiet ways people build lives—rooted in the belief that curiosity and pluralism are this country’s greatest strengths.

After all, behind every technocratic state or litigation nation lies the everyday citizen. Perhaps the truest test of which system “works best” is found in those who had a choice of where to build a livelihood.

“There’s a lot to be grateful for in America,” my mom admitted recently. “Plus, China’s economy isn’t doing so well these days.” Her words, though pragmatic, feel conditional—her sense of contentment fluctuating with the fortunes of two nations. I’m not sure how much they mean. The real vote, after all, lies in her feet.

Had I been born and raised in China, I would not be who I am today. My Chinese-American identity is more than being both Chinese and American—it is the center of my values and worldview. I am cautiously optimistic, action-oriented on the surface, quietly deliberative beneath it. My experiences have made me more empathetic toward the underdog, more wary of exclusion.

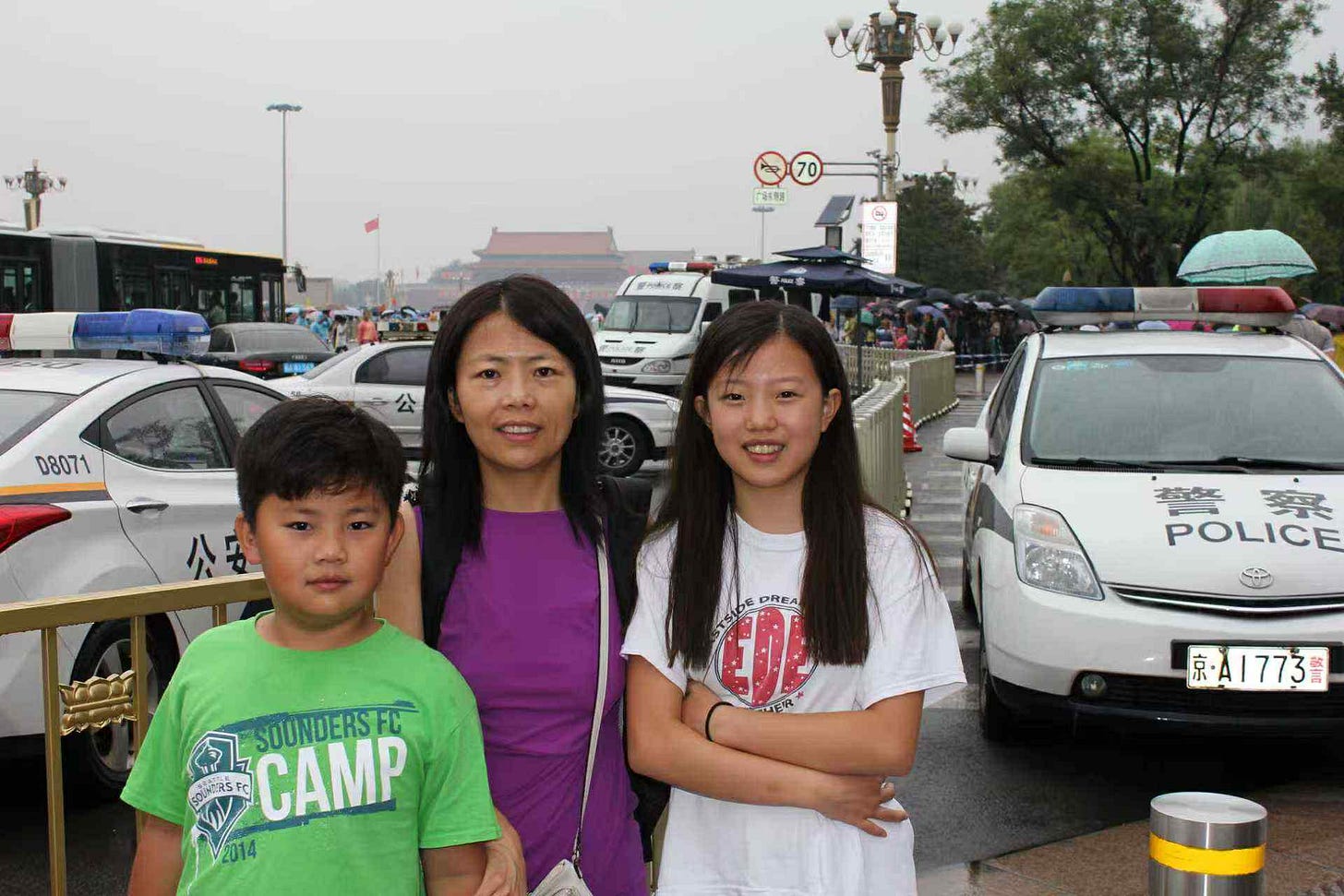

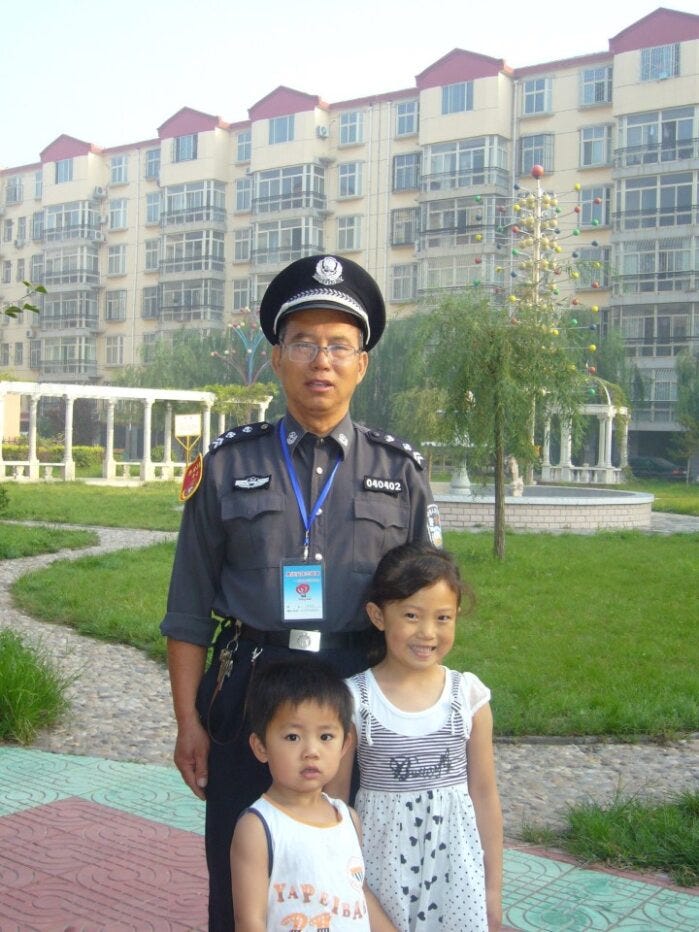

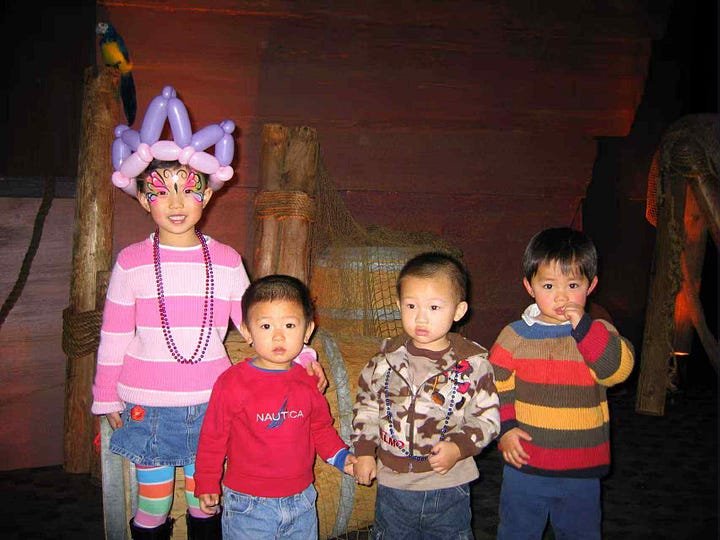

In the absence of extended family, we built our own kinship here. Guanxi—the Chinese notion of relationships and reciprocity—lives on in the potlucks we share with three other immigrant families. For nearly twenty years, we’ve grown together: ski trips and lakeside vacations, job changes and citizenship ceremonies, elderly passings and newborns. I’m the first to graduate and start a professional life; four are in college now, two in high school. Yet when we return home for the holidays, my mom’s bing (Chinese flatbread) and Mr. Yang’s yangrouchuan (lamb skewers) will always be waiting. My brother will eat too much until my mom scolds him; the Aunties will pry about my dating life; my parents will send everyone home before ten (not every family plays mahjong till dawn).

And then we’ll meet again next year—and the next. It gets harder each time to gather everyone, but we always find our way back, to Bellevue, Washington, United States of America.

Techno-optimism feels particularly relevant given the recent Nobel prize, rewarded to research about technological progress and creative destruction as necessities for sustained economic growth. Read more here: